All models are wrong

CRDT implemented using Typeclass

April 17, 2022

Overview

This article shows how to implement CRDT using typeclass in Scala 3. I used this exercise to learn more about CRDT, while picking up some new features from Scala 3.

For readers who are unfamiliar to CRDT, CRDT is a kind of data structure that are replicated (typically across network), they can be updated independently and is guarantee to converge eventually without the need of a centralized controller (ie. a server).

One of the most common use case is collaborative text editing.

To learn more, I recommend this survey study: A comprehensive study of Convergent and Commutative Replicated Data Types.

Note all source code used in this post can be found here.

CmRDT Algebras

CmRDT (Commutative Replicated Data Types) is a type of CRDT, it is sometimes called op-based CRDT. The key characteristic of it is that changes on data are synced by operations instead of sending the whole state. This is in contrast with CvRDT, which sync by sending the whole state over the network, there are some trade-off between these 2 types, but we wont delve into them in this piece.

We will explore the algebra of CmRDT, and encode them in Scala 3.

To fully define CmRDT and corresponding algebra, we need to define a few concepts:

Staterefers to data structure that represents CmRDTLocal Copyrefers to CmRDT’s state that is local with respect to the operationsLocal Operationis data structure that represents operations on a local copyRemote Copyrefers to CmRDT’s state that is remote with respect to the operationsRemote Operationis data structure that represents operations on a remote copy, and need to be sync to a local copy

Before defining the algebra, let’s go through the overall flow informally just to get a feel of CmRDT, I will use the most trivial CmRDT as a example, which is a Counter.

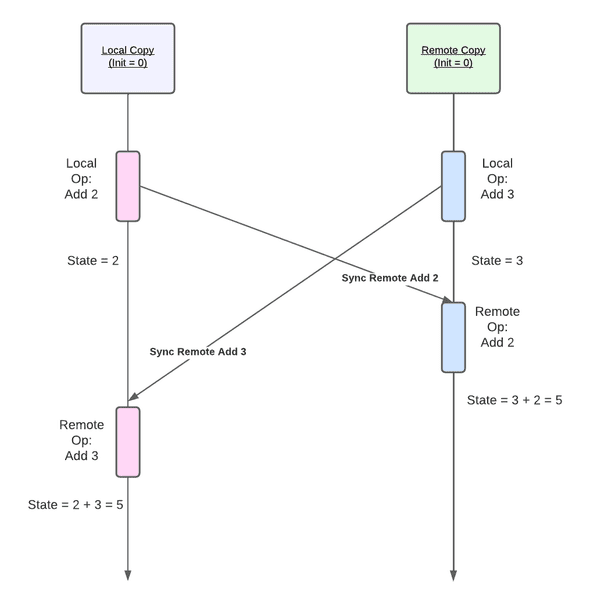

We can view this sequence diagram from top to bottom.

- The system contains 2 data structures, replicated, labeled as Local copy and Remote copy respectively, both initialized to 0.

- Local copy performs

Add 2operation, changing state from 0 to 2 - Concurrently, Remote copy performs

Add 3operation, changing state from 0 to 3 - Local copy send

Add 2operation to remote copy - Remote copy apply

Add 2, changing state from 3 to 5 - Remote copy send

Add 3operation to local copy - Local copy apply

Add 3, changing state from 2 to 5 - Finally, both copy are in sync and have the same value as 5

From the flow above, we can notice that local operations can happen concurrently, they will then need to be sync to remote copies, in this process, the order of operations are not the same in different copies, but we should still get the same result. This property is known as Commutative, which is where the name comes from.

Now, we can enter the algebras and constraints, it can be distilled into the following rules:

localChangeoperation, this applies aLocal Operationto aLocal Copy, it will update the local statesyncRemoteoperation, this applies aRemote Operationto aLocal Copy, it will update the local statelocalChangeandsyncRemoteshould be commutative, the order of applying them shouldn’t matter

Encoding Algebras in code

Now that we have the algebra, let’s encode them in Scala, I am using Scala 3, I will try to be as abstract and precise as possible.

trait CmRDT[A] {

type RemoteOp

type LocalOp

type ProjectValue

extension (a: A) {

def syncRemote(op: RemoteOp): A

def change(op: LocalOp): (RemoteOp, A)

def read: ProjectValue

}

}Here, we model CmRDT as a typeclass, let’s inspect all elements:

- type param

A, we are implementing it as typeclass, soArepresent any data type that can be CmRDT RemoteOptype member, this represents all possible Remote OperationsLocalOptype member, this represents all possible Local OperationsProjectValuetype member, this wasn’t mention on the section above, it represents the value we want to read from CmRDT without all of the metadata, its purpose will be more apparent later when we look at testing-

All 3 methods are implemented as extension methods, this is a new feature from Scala 3

syncRemoteapplies aRemoteOpto a local copy, and return a new A, this means it can be implemented as pure functionchangeapplies aLocalOpto a local copy, it returnsRemoteOpandA, it returnsRemoteOpbecause for every local operation applied, we need to apply a correspondingRemoteOpto remote copies, which will come from this methodreadreturns theProjectValue, this is useful because sometimesAcan be a relatively complicated data structure that stores metadata like nodeId etc, but our consumer code only care about the projected value, for example, an array or a set.

These is all we need to describe a CmRDT without committing to specific implementation details. Encoding algebra as typeclass allows us to verify checks against it.

Implementing test using encoded algebra

How do we test CmRDT? The rules are quite simple, we just need to make sure operations are commutative, ie. the order of operations does not affect the final results.

Informally, we can encode it as f(g(x)) == g(f(x)) where x is the State, and f and g are both operations.

Now we want to implement these rules using automated checks, let’s start with pseudo-code:

- Initialize a collection of

NCmRDT to the same value, for each CmRDT we also need to keep a buffer of remote Op, initialized to empty buffer - Randomly pick one of the data structure A

-

Randomly choose between performing a local change, or syncing a remote operation

- Note that we will need the ability to randomly generate a local change, this is where property-based test framework like Scalacheck comes handy

- We dont need to randomly generate Remote operation, because they are produced by

def change(op: LocalOp): (RemoteOp, A) - If there’s no remote operation to be sync for

A, it should be no-op

- If we decide to perform a local change, we will generate a local operation, apply of

A, then store the correspondingRemoteOpalongside every other copies - If we decide to sync remote operations, then we should randomly consume

Qremote op from the remote Op buffer, and apply them one by one toA - Repeat step 2 to step 5 for

ktimes - Then we should clear all remaining

RemoteOpin each CmRDT’s remote op buffer, this is to ensure we eventually applies all operations to all copies - Assert that all CmRDT copies return the same value from

readoperation, here we can finally explain the purpose ofreadoperation, the rule here is that all CmRDT copies must converge to the same value, but they only have to converge on their ProjectValue, not necessarily everything, and this is captured byreadoperation

Now, we can see how it works in code, we will start by declaring a test module

import cats.data.State

import cats.Eval

import cats.syntax.all._

import cats.instances.list._

import org.scalacheck._

import org.scalacheck.rng.Seed

trait CmRDTTestModule[Data](initData: List[Data], seed: Long, repetition: Int)(using val crdtEvi: CmRDT[Data]) {

def localOpGen(dt: Data): Gen[crdtEvi.LocalOp]

case class TestState(

seed: Seed,

dataWithNetwork: List[(Data, UnreliableNetwork[crdtEvi.RemoteOp])] = List.empty

)

}Thanks to Scala3, traits can now take parameters, Data refers to the CRDT types, and initData is the collection of initial values, seed is passed in as well, so that we can simulate randomness deterministically, repetition: Int controls the no of loop we perform.

The traits also expect val crdtEvi: CmRDT[Data], to prove that Data is CmRDT. There is also 1 abstract method def localOpGen(dt: Data): Gen[crdtEvi.LocalOp] that should be implemented by concrete implementation, this allow us to generate LocalOp, the method takes a Data as input because sometimes we can only generate valid LocalOp with respect to existing state, for example in a KV store, it might be invalid to delete a non-existing key.

Then we have an inner case class TestState, it represents all the state within the test flow, worth noting that it contains a list of (Data, UnreliableNetwork[crdtEvi.RemoteOp]), each tuple represent one CRDT with its corresponding RemoteOp buffer.

UnreliableNetwork is a buffer of RemoteOp, it has some helper methods to help us manage the state. For simplicity, I wont show the full definition here.

Now let’s look at the actual flow:

trait CmRDTTestModule[Data](initData: List[Data], seed: Long, repetition: Int)(using val crdtEvi: CmRDT[Data]) {

.....

def opsAreCommutative: Unit = {

val randomizedLoop: State[TestState, Unit] =

(0 to repetition).foldLeft(State.empty[TestState, Unit]) { case (st, _) =>

st.flatMap(_ => randomLocalChangeOrRemoteSync)

}

val (resultState: TestState, _) =

randomizedLoop.flatMap(_ => clearRemainingRemoteOps()).run(initTestState).value

val finalData = resultState.dataWithNetwork.map(_._1.read)

assert(finalData.toSet.size == 1)

}

}def opsAreCommutative is our assertion method, before looking into the implementation, I wish point out that I implemented the flow using State Monad, this allows us to model state mutation without side effect. It is easier this way because everytime we generate a random value, we need to mutate the Seed value to ensure the whole flow is deterministic. It is entirely possible to do without State monad and just mutate variable local to the trait, I just didnt do it that way.

Now let’s look at the method, really it just performs 3 steps:

- Randomly perform local change or remote sync for

repetitiontimes,repetitionis a Int argument, every time we will randomly pick a copy from all CRDT values - Clear remaning remote ops for every CRDT data

- Check that all CRDT data converges

I wont show all of the code for this test module because they are too noisy, if you’re interested, you can find them here

I think the more interesting part is that once we’ve implemented the TestModule in an abstract way, we can reuse the same test implementation to many different CRDT implementation with low overhead.

Let’s look at the simplest CRDT, Counter, it is implemented this way:

opaque type Counter = Double

object Counter {

def apply(d: Double): Counter = 0.0

extension (x: Counter) {

def value: Double = x

}

given counterCRDT: CmRDT[Counter] with {

type Increment = Double

override type RemoteOp = Increment

override type LocalOp = Increment

override type ProjectValue = Counter

extension (counter: Counter) {

override def syncRemote(op: Increment): Counter = counter.value + op

override def change(delta: LocalOp): (RemoteOp, Counter) = {

delta -> (counter.value + delta)

}

override def read: ProjectValue = counter

}

}

}Here, we implement Counter as an opaque type, this is another new feature of Scala 3. Basically we are saying Counter is a Double, but it can only be modified using methods defined here.

We can see that the RemoteOp and LocalOp are the same, and they are just Increment. Then we can use our TestModule to test Counter this way.

test("Counter is CRDT") { () =>

val counterIsCrDT =

new CmRDTTestModule[Counter](

initData = List(Counter(0.0), Counter(0.0), Counter(0.0)),

seed = 1000L,

repetition = 20

) with Expectations.Helpers {

override def localOpGen(dt: Counter): Gen[crdtEvi.LocalOp] =

Gen.double.map(_.asInstanceOf[crdtEvi.LocalOp])

}

counterIsCrDT.opsAreCommutative

}Here we define CmRDTTestModule for Counter, and all we need to provide are initData seed, repetition and localOpGen, they can all be provided trivially. Then we just need to execute the assertion method to verify that our Counter CmRDT is implemented correctly.

Let’s look at a 2nd example of CRDT, Multi-Value Register, it is a very simple data structure that represents a single value, the special thing is that it can detect concurrent edit, and when this occurs it will keep all concurrent values and allow reader to resolve the conflict.

It is represented using this fairly simple data structure

case class MVRegister[A](

pid: ProcessId,

existing: Set[(A, VersionVector.Clock)],

clock: VersionVector.Clock

)The full implementation of MVRegister CRDT is available here.

Then we can look at the test

test("MVRegister is CRDT") { () =>

val registerIsCRDT = new CmRDTTestModule[MVRegister[Int]](

initData = List(

MVRegister[Int]("1", 0),

MVRegister[Int]("2", 0),

MVRegister[Int]("3", 0)

),

seed = 1002L,

repetition = 20

) with Expectations.Helpers {

override def localOpGen(dt: MVRegister[Int]): Gen[crdtEvi.LocalOp] =

Gen.long.map(_.toInt.asInstanceOf[crdtEvi.LocalOp])

}

registerIsCRDT.opsAreCommutative

}We can see this test is very similar to the one we had for Counter, the main difference is the initData which is trivially different, and localOpGen is implemented differently.

So we now have a very cheap way to test all CmRDT, provided that we can implement CmRDT[A] typeclasse for the type.

Conclusion

I hope this exercise shows the usefulness of distilling a problem into its absolute essence and encode into using a powerful expressive type system.

It helps us to reason about problem and solution without much noise, for instance, we know that for a type to be a CmRDT, it needs to provide 3 methods and fulfill the commutative property of 2 of those methods. We can then compose these algebra to that provides interesting properties, an example here is our ability to leverage the typeclass to implement property check.